You know the story. Textile waste is one of the largest causes of pollution on the planet.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that Americans alone generate more than 15 million metric tons of textile waste annually, which is about 104 pounds per person per year. And we’re not just talking about clothing. Textile waste includes everything from canvas boat covers and awnings to shade sails, sheets and hospital gowns.

Only about 15% of that is collected for resale or recycling. The remaining 85% is directly discarded in landfills or incinerated. Landfill waste creates methane which is over 20 times more damaging than CO2 and can leach toxic chemicals and dyes into the groundwater and soil.

Sure, there are recycling centers across the country that will take old clothing and fabrics, but only about 20% of textiles donated to these facilities are resold domestically, as they take in far more donations than they can handle.

What happens to the rest? It is often incinerated or ends up in a landfill. Otherwise, it gets ground up and used as stuffing or insulation or is turned into cheap wipes. Sometimes it can be recycled into new clothing.

Major apparel brands such as Patagonia, H&M, Northface and others have programs to reclaim their products for various uses. Madewell, for example, has partnered with the Blue Jeans Go Green program and Habitat for Humanity to recycle donated jeans into housing insulation.

But other companies are taking it a step further by not just recycling used textiles but breaking them down into their components and turning them into new fibers. These are then woven into new fabrics (which, at the end of their lifecycle, can be processed again and again). That’s true circularity. Here’s a look at three of those companies.

Infinited Fiber

Helsinki, Finland-based Infinited Fiber is a fashion and textile technology company founded in 2016 to commercialize technologies that use waste materials as feedstock. The company’s premier product is Infinna thread which it sends to either yarn or nonwovens producers.

“We break waste down and capture its value at the polymer level, giving it new life as Infinna textile fiber that looks and feels like cotton,” says Tanja Karila, the company’s chief marketing officer. “The technology we use for creating new fibers from recycled textiles is a specific cellulose carbamate [CCA] technology. It enables converting cellulose-based materials, such as textile waste, into a high-quality premium regenerated textile fiber and creates value in closed-loop textiles. In short, Infinited Fiber technology and the patented solution offer a possibility to turn waste streams into affordable and sustainable textile fibers,” she says.

While Infinited Fiber currently focuses on using cotton-rich textiles, the technology can also turn other cellulose-rich materials, such as old newspapers, used cardboard and crop residues like rice or wheat straw, into the same fiber.

“All cellulose-rich waste streams can be used,” Karila says, “but the pre-treatment part differs. Only cellulose is captured for the final process phase, so the quality of the feedstock is essential. Currently, we mostly use textile waste with 88% to 90% cotton content. A small percentage of elastane is also acceptable if the cotton content is high enough. Cotton is the cellulose that we use in our process.”

Earlier this year, the company achieved certification for recycled content under the SCS Global Services Recycled Content Standard. Infinna textile fiber is certified as having a minimum of 99% post-consumer recycled content.

Circ

Based in Danville, Va., Circ says its goal is “10/10/100.” That is, the company aims to recycle 10 billion garments, representing 10% of the global apparel market, which will save more than 100 million trees.

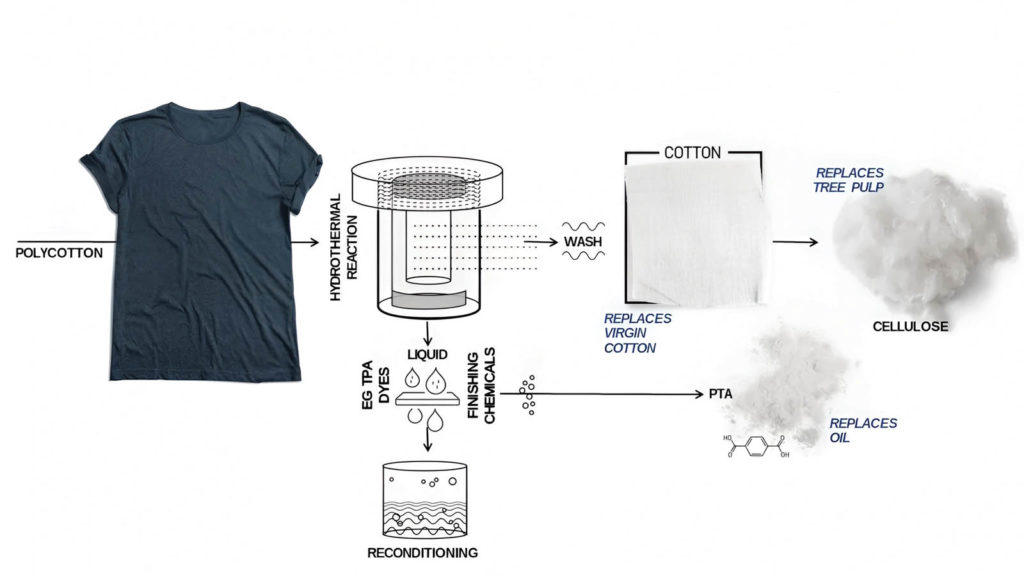

“One of the big problems out there is what to do with the blended textiles,” says Julie Willoughby, Circ’s chief scientific officer. “When you have different polymers combined it makes recycling harder. And one of the favorite textiles out there that we use in all our clothes are polyester-cotton blends” she says.

Cotton is far more expensive than polyester, so manufacturers blend in polyester to bring that price down. About 65% of textile waste is a poly-cotton blend.

“Right now, the only thing you can do with that is to downcycle it,” says Willoughby. “It goes into shoddy fibers or insulation—and these are all great uses, so it’s still better than sending it to a landfill or burning it.”

But Circ can recover both the polyester stream and the cotton stream. “We do that by our hydrothermal technology process that liquefies the polyester so the cotton can just be spun out. We extract these two components, and we can make new cotton fibers or new polyester fibers out of poly-cotton textile waste,” Willoughby says. “We can use them over and over again—that’s true circularity without impacting new raw materials. I have calculated that, based on the amount of waste that we have processed, we’ve recycled the equivalent of 200,000 T-shirts this year alone.”

As Circ’s website notes: “We have all the clothing we need to make all the clothing we’ll ever need.”

Not every fabric can be processed, Willoughby says. “Not all coatings are created equal. If you put in a really high-gloss, acrylic-coated polyester, it’s going to come out as gunk. So, we just filter that out of the process. The unique thing about our process is we can take anything from 0% polyester to 100% polyester.”

At a recent energy summit, Willoughby learned that the process of producing cement contributes 5% to greenhouse gas emissions. “That’s a huge problem,” she says, “but the apparel industry contributes 10% to greenhouse gas emissions. People don’t really realize how much that is. We must do something to change that.”

Evrnu

Stacy Flynn had worked in the textile industry for many years for such companies as Eddie Bauer, Target and DuPont, but in a 2015 TedX talk, Flynn said she felt partly responsible for the textile waste problem. “I found myself standing in the middle of a massive industry problem that I helped to create. I was pissed and incredibly well trained and decided to dedicate the rest of my career to finding solutions.”

Flynn partnered with Christopher Stanev, a textile engineer who held numerous patents for processing textiles into their components and creating new fibers. In 2014, the two launched Evrnu, based in Seattle, Wash. Evrnu multiple lifecycle fiber technologies are used to create engineered fibers with performance and environmental advantages, made from discarded clothing.

“We just cracked the code and got a fiber that is just as strong or stronger than petroleum-based options by using a plant-based backbone, which means nature knows how to break it down,” says Flynn.

Given the number of petroleum-based fabrics used to make clothes today, “we have a direct replacement for 60% of the market,” Flynn says.

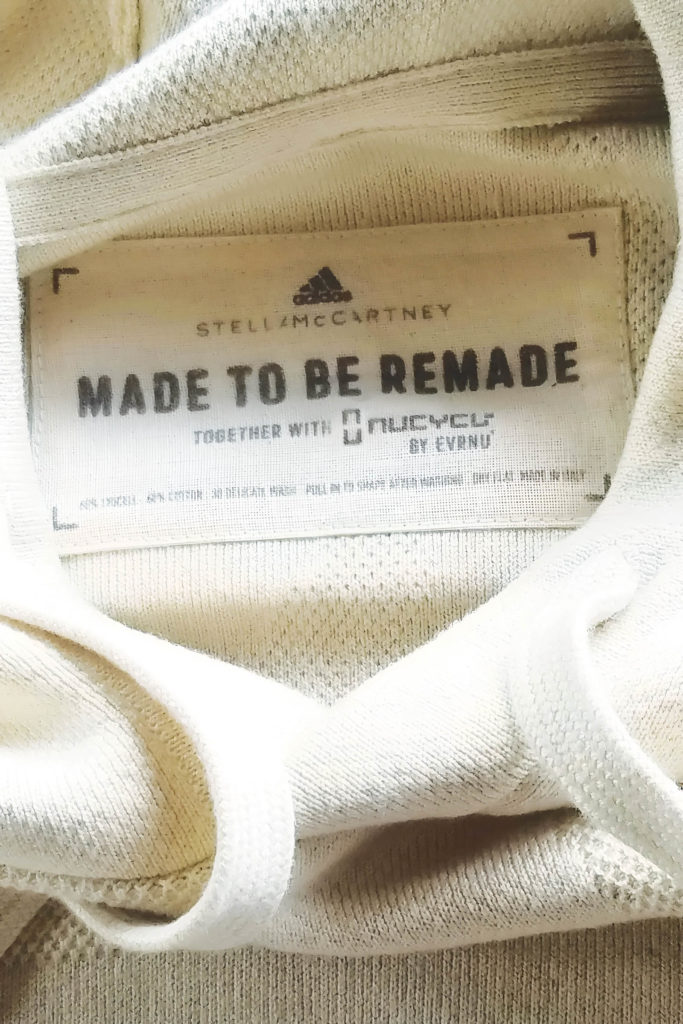

A big win with such technologies is they keep materials in constant play, dispensing with waste. Evrnu and the companies mentioned above are in various stages of utilizing these so-called closed-loop technologies as they produce fabrics that can be constantly remade into new garments.

Evrnu’s first commercially available fiber is called NuCycl. Products made with NuCycl can be disassembled to the molecular level and regenerated multiple times into new clothing or home and industrial textiles. The technology uses repolymerization to convert the original fiber molecules into new high-performing renewable fibers. The company says that even the toughest type of textile waste—100% post-consumer—can be turned into new materials with NuCycl.

Tim Goral is the senior editor of Specialty Fabrics Review.

SIDEBAR: The educated consumer

Circularity can only work if everyone participates, and that means consumers. When people discard clothing, for example, they will often bring it to a consignment or thrift store. Their intentions are good, but the fact is that much of it still ends up in a landfill because it is damaged or otherwise unusable. So how can consumers be persuaded to get on the circularity bandwagon?

“This is an important and complex question,” says Tanja Karila of Infinited Fiber. “Manufacturers must be transparent, and design for circularity. But more importantly, they must communicate about recyclability and the value of recycled products. Consumers also need to know about post-consumer textile sorting–what can be recycled, what can’t, and how to dispose of those textiles.”

And while the circularity goal is attainable, at least on paper, it will take educating consumers to really get the ball rolling.

“I think it’s important for every consumer to understand how their clothing is made, but I also believe it’s important for them to understand where the goods they’re buying come from and where they would end up at the end of their lifecycle,” says Circ’s Julie Willoughby. “For the average consumer, I think it is going to take some time. While we don’t want a green premium on the clothes that are made with our technology, there likely will be one in the beginning. As we scale and as manufacturer scale that green premium is reduced.”

Leave A Comment