The advantages of diversification are well-known. Serving multiple markets can help a business grow, and when one market experiences a downturn, other markets can help prop up a company. According to the 2021 State of the Industry report published by Industrial Fabrics Association International (IFAI), more than half (56 percent) of specialty fabrics businesses plan to enter new markets in the coming years, and most already serve an average of six markets.

But going after new sources of business has risks. The business leaders interviewed for this article have moved into new markets by acquiring other companies, shutting down one revenue stream to grow another and investing in new equipment. They’ve also seen benefits even when a foray into a new market didn’t work out. In the end, the rewards for attempting to move into new markets—more stability, business acumen and, of course, profit—are worth it.

Many markets, one product type

InCord, a custom netting fabricator based in Colchester, Conn., is no stranger to serving diverse markets, listing more than a dozen on its website—including construction, theater and fleet maintenance facilities. The common denominator is that all need safety netting, whether to contain debris on a construction site or prevent actors and props from falling into the orchestra pit at a theater.

CEO Meredith Shay says the diverse market mix helps balance fluctuating demand—when one industry slows down, another might pick up. The company started with amusement parks, construction sites and warehouses, and has added others along the way. InCord takes a methodical approach to expansion. “It takes us a long time before we jump in,” Shay says. “There has to be a need, and we have to have a solution.”

In some cases, InCord has acquired smaller companies to get a foothold in a new area, as was the case with the recent purchase of East Coast Lifting Products, a custom web sling manufacturer serving the rigging industry. Shay explains that the companies had similar business models, with both offering safety-oriented custom textile products.

InCord also discovers new markets through its sales representatives, who look for opportunities by networking and attending trade shows for industries not currently served by InCord. Shay says that sometimes these efforts uncover potential, and other times they don’t pan out.

“Agriculture was one market we chose not to pursue because we discovered their netting needs were more of a commodity for growing plants rather than safety,” Shay says. “But that may change in the future, so it was time well spent.”

Although InCord’s salespeople are assigned to specific markets, the production staff is cross-trained and can work across different categories. That way, when demand is down in a particular segment, production can shift to more active markets, while the salesperson for the down market can use the time to build relationships and explore new products.

Occasionally, the company has been tempted to go outside its wheelhouse to serve a market. One recent example was producing hospital gowns during the pandemic, which the company halted once it realized it couldn’t be competitive. “There’s a silver lining every time we fail,” Shay says. “It’s an opportunity for people in the organization to develop their skills, both technical and managerial, and shine. And sometimes they didn’t even know they had it in them until the opportunity presented itself.”

Leaping and learning

Attempts to enter new markets can help clarify priorities, as was the case for RBH Designs LLC, which attempted to get into the personal protective equipment (PPE) market in 2020. Based in Tolland, Conn., the company designs and produces performance apparel and accessories using its proprietary VaprThrm® technology. The unique vapor barrier system keeps insulation dry from the inside for outdoor sports enthusiasts such as mountain climbers and skiers. The company has sold to consumers via its website since 1998.

In early 2020, owner Ryan Hannigan recognized a connection between technical outdoor clothing and PPE, as both require vapor barrier film suppliers. Hannigan thought RBH would be well-poised to jump into the PPE market, as many government and health care operations were signaling a desire to return to domestic production of PPE, even post-pandemic.

RBH took the leap, leasing a 3,000-square-foot commercial building and purchasing new equipment, including an ultrasonic welding machine and hot air seam taper, to accommodate PPE production. The moves proved to be a bit hasty, according to Hannigan.

“The reality is the PPE market is a price-sensitive, high-volume business, and we’re a very small shop,” he says. That lesson helped clarify Hannigan’s thinking about what RBH’s competitive advantage was.

“We’re a [business to consumer] company that specializes in protection, primarily in cold weather with our made-to-order VaprThrm technology, and we use our 23 years of experience and capabilities for product development,” he says.

The jury is still out on whether RBH will see a favorable return on investment on the additional square footage and equipment, but the company is using the machines on custom projects and to waterproof its own garments.

“We’ve been fortunate to adapt and find new customers,” says Hannigan. This new work includes sewing covers for a client’s high-end outdoor furniture, radio frequency shielding products, aviation headset components and awnings. The company’s outdoor apparel sales also grew as more consumers pursued outdoor activities during the pandemic. The benefits of having additional square footage have been realized in the additional volume of work RBH has been able to take on. “It’s nice to have room to spread out,” Hannigan says.

Cutting one revenue stream to grow another

When people ask Matt Guthrie what his company, SuperiAire Technologies LLC, does, he replies, “We play with bombs and parachutes.” Of course, it’s more complicated than that, but he’s learned that the real answer takes too long to explain. A lifelong hot-air balloon enthusiast, Guthrie started his business in 1998 as a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Certified Repair Station, a rigorous certification that allowed the Albuquerque, N.M.-based company to repair and maintain hot-air and gas balloons. Guthrie’s ultimate goal was to work on government contracts, but he knew the repair station would generate immediate cash flow and could sustain the business while he pursued government contacts and contracts.

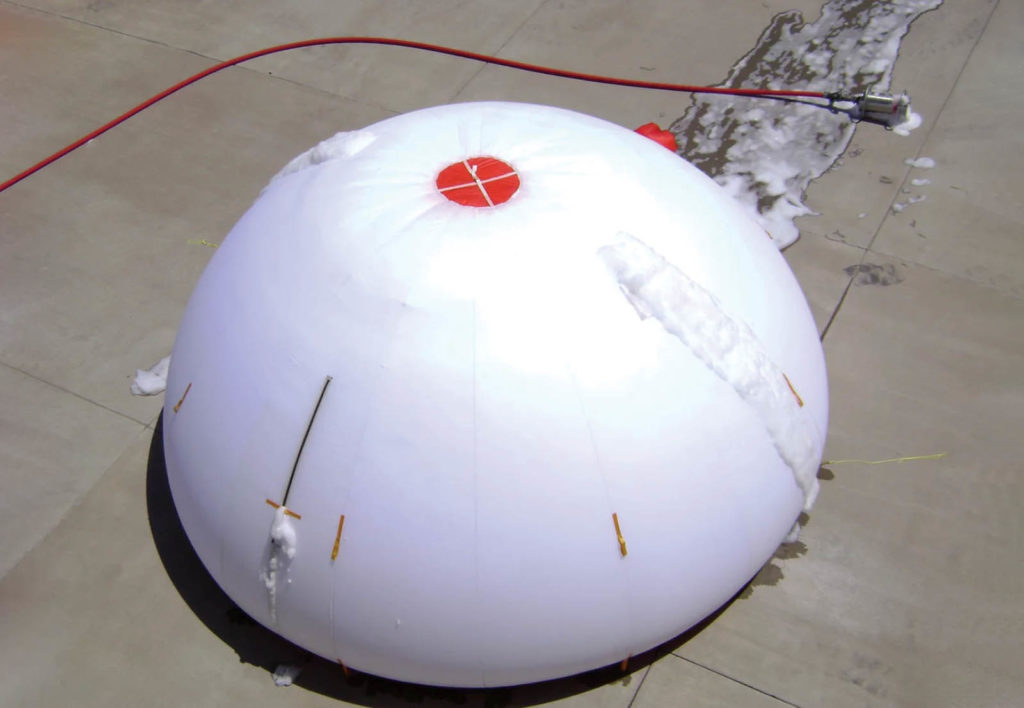

SuperiAire eventually found a foothold in parachutes and fabric blast attenuation devices (devices used by first responders and bomb squads to reduce the damage caused by an explosive). The company’s FAA certification was an advantage because it already had stringent quality checks in place—a requirement for federal contracts.

In 2010, when the company had built up a reliable stream of government work, it took what Guthrie describes as a “pretty frightening” step and closed the repair station to the public. “It became too difficult to run both businesses under the same roof, and we were almost too busy to work on the side that had the best future,” he says.

Closing the repair shop also had the benefit of cutting down on labor hours spent cleaning and maintaining the workshop and sewing machines that would get dirty from balloons that had landed in the dusty New Mexico desert. Employees were happier, too, according to Guthrie.

With the increased government work, SuperiAire had to purchase additional equipment to improve productivity, such as an Autometrix computerized cutting table. The sewing staff was skeptical at first, worried the machines would replace them, but they soon realized the machines made their jobs easier. Some training was required on assembling the new products, but most skills and procedures transferred over.

Guthrie is gratified to see his business develop according to plan. “We wanted to produce government products from day one,” he says. “When we eliminated balloon repair, some people said, ‘Oh, sorry to hear you’re out of business.’ We weren’t out of business. We just changed our business. And there’s no way our balance sheet would be as healthy if we hadn’t.”

Chaos and capabilities

When asked about Rogue Powersports and Paradigm Textiles LLC’s recent foray into the protective apparel market, CEO J Michael Johnson puts it bluntly: “COVID caused a lot of chaos.” The Dallas, Texas, manufacturer of windscreens for utility task vehicles (UTVs) was called into service in early 2020 to help produce PPE for a large hospital system in Dallas that was desperate for isolation gowns and sought help from local companies. “They found a group of 16 [different companies], and we made half a million gowns,” Johnson says.

At first, Rogue Powersports thought this might represent a permanent new market, based on what many were saying at the time about keeping manufacturing in the United States in the future. It didn’t work out that way. “Boy, has that not been true,” says Johnson. “Most of them have gone back to foreign suppliers because they can produce an inexpensive product.”

However, while Rogue Powersports was sourcing raw materials for PPE gowns, the company learned of other industries seeking domestic production, including a company that makes coats for meatpacking plants and other cold storage environments.

Using the company’s CAD system, Rogue Powersports was able to re-pattern and digitize the customer’s design, make samples and eventually produce the apparel. And this customer has not returned to overseas suppliers.

Rogue Powersports has been careful to rely on its network of contractors and firms with specialized capabilities to produce the products to avoid purchasing new equipment or making additional hires.

“We can test the market without having to make a huge capital investment,” Johnson says. “We primarily do the design and prototyping in-house, and once we’ve developed the product design, we can go to one of our subcontractors and have them assemble.” This gives Rogue Powersports flexibility and time to evaluate the potential of new markets and products.

Because the protective apparel market is so different from the off-road vehicle market, Rogue set up a sister company, Paradigm Textiles, to handle contract prototyping and the sewing business, complete with its own branded website. Johnson’s advice to others seeking new markets is to be cautious and don’t overextend.

“Promises don’t always come true, but this experience opened up doors we weren’t aware of and capabilities we hadn’t thought of,” he says. “There’s a lot of things we can do now.”

Businesses in the specialty fabrics industry have always worked in multiple markets and kept an eye open for new opportunities. Of course, not every new market will be successful for every company—as the temporary PPE market during the pandemic has shown. But not being open to taking risks and stretching capabilities is a risk in itself. Business leaders who know what their company does best (or what it could do best, with the right equipment and workforce)—and how those capabilities can solve someone else’s problem—are on their way to discerning whether the reward of a new market is worth the risk.

Laurie F. Junker is a freelance writer based in Minneapolis, Minn.

SIDEBAR: PPE: A temporary pivot or a lasting opportunity?

In 2020, many companies that had never worked in the health care textiles market turned to personal protective equipment (PPE) to keep their doors open, regardless of the long-term payoff. If you are tempted to stay in the PPE market, what do you need to know?

“When you’re talking PPE, you’re talking FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] certification, and that’s a whole different ball game,” says Frank Keohan, senior technology manager for Bolger & O’Hearn Inc., a textile chemical manufacturer based in Fall River, Mass. It’s a lesson he repeated often in 2020 when textile companies reached out for help getting into PPE. The 50-year-old chemical supply company understands this market well, particularly the durable water repellent (DWR) specifications for various classes of PPE.

“There are specifications for medical-grade textiles, which need to act as a barrier to liquid penetration while preserving some breathability at different levels depending on where the garment is used,” Keohan explains.

Hospital gowns are assigned a level indicating their liquid barrier protection capabilities. For example, garments worn for basic care or by hospital visitors have a Level 1 designation, while Level 4 gowns are appropriate for surgeons.

Bolger helped several companies determine which level their business was best suited to produce, which fabrics and coatings would work for that level, and how to set up processes and testing to meet FDA standards—steps that take time but can pay off in the long run, according to Keohan. “Once you have the pieces in place, you may have some stability because it’s that much more difficult for others to overcome the barrier to entry.”

Leave A Comment