A successful work of public art today should not be treated as an object sitting in the environment; rather it should be interpreted as the environment.

—James Wines, American artist and architect

James Wines is known as a provocative artist who creates building-sized installations that some would say are more architecture than art. Indeed, he wrote a book about the fusion of these two artistic expressions called De-architecture, where he insisted that “buildings don’t need a defensive rationale to explain their existence,” but that if art wants to claim the attention of any public space, it should be raised to the same regard, and it should engage fully.

Frequently, it may seem that the most common public spaces seen in any consistent fashion are concrete highways and parking lots, with very few public spaces that cause us to want to linger. Solid walls, glass-enclosed office buildings or stores, concrete sidewalks—many of these transitional spaces could use improvements that are uplifting. A few recent architectural fabric projects are helping to turn this condition around.

A case in point is the new Salt Lake City International Airport terminal that opened in September 2020. Designed by HOK architects and embellished by a glorious fabric art installation by public artist Gordon Huether, the new terminal upgrades the city’s 60-year-old airport facilities. Huether—with the help of an expert team of fabric structure specialists: Rainier Display, Pfeifer FabriTec and Charles Duvall Design Inc.—created “The Canyon,” a dynamic fabric construction that is prominently on view in the main concourse where thousands of passengers scurry by each week on their way to departure gates. The main terminal project scope for HOK included 4 million square feet of facility improvements, including wayfinding guides (such as “The Canyon”), and artistic seating areas that make the transitional experience much more pleasant.

In fact, people regularly pause to take in the fabric art, and since its opening in late September, an upper-level pedestrian bridge that crosses the concourse hall has become a favorite spot for selfies, as the artwork transfixes commuters in their tracks. Says Huether, “It is my strong opinion that the most successful large-scale public art is about the place, the mission and the art itself—not the artist.” Huether, a Napa, Calif.-based artist specializing in large-scale, site-specific art installations, was inspired by the way Utah’s nature replaces itself and gradually changes over time, says Rainier Display’s Bruce Dickinson, vice president for business development. “The installation is meant to evoke Utah’s natural landscape of unique geological formations.”

A team coalesces

For the team, “The Canyon” was almost five years in the making. Beginning with the Salt Lake City Department of Airports (SLCDA), “the prime objective from the start was to celebrate the natural beauty of Utah in a full, architecturally integrated art program,” says Huether. “The result is a series of installations, each telling a different story about Utah’s environment: ‘The Canyon,’ a ‘Canyon 2.0’ [for Phase 2 North Concourse], and ‘The River Tunnel’ [for a Phase 3 connecting tunnel between the main and north terminals].”

Established working relationships played a strong role in the formation of a team to see the original vision through to final installation. HOK, the architects of record, had a number of airport designs and renovations in its portfolio. The SLCDA engaged Huether, based on his previous work on other large-scale projects through the national Percent for Art mandate on publicly funded building projects.

As to the fabrication and installation team, membership in Industrial Fabrics Association International (IFAI) proved to be the connecting tissue: Rainier Display and Pfeifer FabriTec Structures, when bidding on the project, soon realized that they would be competing against each other and that it made more sense to collaborate, since neither could do the entire job without the skills and resources of the other. They in turn engaged Charles Duvall Design to translate the artist’s sculpture into fabric shapes mounted on bent aluminum tubing, a fabric display industry standard.

“The project has been so complex,” says Gary Taylor, marketing director for Pfeifer FabriTec, “that it has been hard to determine when one person’s scope of work ended and it crossed over into another person’s.”

Complexity of forms

Huether had initially thought to build “The Canyon” sculpture out of rigid materials, and in fact had produced several scale models using hard materials. When Rainier’s Dickinson first met the artist and saw the mock-ups, he wondered, “How are we ever going to produce this?” About that time, Charles Duvall was invited into the conversation. “I was in Napa Valley and on a project with Claude Centner of Pfeifer FabriTec, and Claude said that there was another job just 15 minutes away. That’s when he invited me to meet with artist Gordon Huether and we got to talking about how the fins of his art piece for SLCA might be fabricated using tensioned fabric.”

Looking at the finished work, it is clearly a highly complex, articulated series of shapes made up of thin fin-like elements meant to remind travelers of Utah’s rain-washed and eroded rocky landscape. Switching to stretched fabric on bent metal tubing seemed a logical way forward to finishing the project as envisioned.

“Within the overall challenge of fabricating this many elements,” says Dickinson, “there was the even greater challenge of figuring out how to produce the deep 3D curves within each fin. We could have done it by hand, and that was initially considered, but it would have taken forever to produce.”

Duvall started with a small fabric and tubing prototype and then was asked to make a series of 13, 30-foot-long fins as a full-scale mock-up. “But after getting it started, I was only able to get half of them completed as some were too complex to complete in a conventional way,” says Duvall. “The fabric forms were less resolved in the beginning because of the complex and compound curves needed to produce the desired shapes.”

He spent several months working on the 13 prototypes in his Rockland, Maine, shop and then moved the effort to Rainier Display’s production floor near Seattle to build fins using its automated cutting tools and working with the shop’s sewing team.

“I had heard about a Tube and Wire show in Dusseldorf, Germany, and suggested to Bruce [Dickinson] that the show might be worth attending, as the Japanese J NEU bender Bruce had seen online was at the show along with numerous other benders,” Duvall says. “So both Bruce and I spent several weeks over that summer examining several free-form bending machines found at the show that could bend aluminum tubing. One that looked promising was a Japanese NEU machine, but when Bruce came across a free-form 3D bending machine from the Netherlands by Dynobend, we felt that we had found the perfect one which actually printed the tube as well as bending it, and we drove there from the Tube and Wire Show after the show.”

Translating the vision

“The hardest part of the project was the 3D bending of the aluminum piping,” says Dickinson. “We were not even sure how to make them when we first got the project. After all, there are some 500 fins in the install.” The Dynobend machine was the game changer, according to Dickinson. But there were still many technical challenges to overcome to get to efficient production.

“There are over 9,000 unique pieces of tubing in this Phase 1 project,” says Duvall. “Each fin fabric is composed of a distinct front and back with about 40 to 50 panels of fabric for each fin.” Each fin is composed of three tube sections: a bottom third, a middle and a top third.

Producing the tube armatures was a multistep process of taking the artist’s individual fin shapes and scaling them up to full size, then converting them into code that could be fed into the 3D tube bender. (See the web-extra technical article Creating ‘The Canyon’ for more detail.) Duvall also did the programming for the files when they went into production. “It was my job to translate the artist’s frame drawings into workable production documents, while retaining the character of the artist’s sketch quality,” says Duvall. “This turned out to be a six-month learning period. The overall time required was 5,000 hours.”

“At Rainier, the machine operator first bends each tube and then tests each tube for precision using a special testing machine which captures the tube centerline,” continues Duvall. “The machine can also ‘learn’ from the error to increase overall precision.” The fabric patterning was done in Mpanel to make sure the tubing and fabric worked together; Rainier took these fabric pattern documents and prepared them for the cutting tables.

Production challenges

When Pfeifer FabriTec took on the project, the original agreement was that the work area in the main terminal would be shut down so that the space was free of other contractors and subcontractors, Taylor says. “But due to the tight construction schedule for the entire terminal, it was kept open. Which meant we had to bring in different lift equipment that could allow us to keep working.”

The work situation led to hardships on the crew’s safety and impediments to efficiency, clearly practical liability issues that Pfeifer FabriTec had to solve.

Installation was methodically organized, working down the full 362-foot length of the main hallway starting at one end. Once these individual fins were assembled and fitted with their unique fabric skin, it was a matter of lifting them up to their unique position. “The only way to keep track of the more than 500 tensile fabric fins,” says Taylor, “was to number mark at top and bottom of the wall surfaces, each fin given a number. The attachment points were actually relatively simple hardware. The key was to clearly put each fin in its designated place.”

The toughest thing, according to Taylor, was for the crew to keep each fin clean. “The white fabric [Tweave® from Gehring-Tricot] could easily have gotten smudged in that work zone with all the other construction going on by the other trades.”

A beautiful finish

There are two more major phases to the Salt Lake City Airport, with Phase 2 to start next year. The team of Rainier Display, Pfeifer FabriTec and Duvall Design already has the jump on the schedule. Phase 2 of the fabric sculpture elements is already done and in storage, waiting until the construction of the smaller North Concourse is ready to accept “Canyon 2.0.” Phase 3, the tunnel, will have an 800-feet-long by 20-feet-wide fabric ceiling constructed in a similar manner as the two Canyon features

of tube and fabric skin.

The result is, “Like man, beautiful!” says Taylor. “The lighting (both daylight and colored night lighting) really sets our project off.” And as hinted earlier, the first phase has proved to be a hit with both travelers and the local community; praise has been strongly noted in newspapers and TV.

James Wines sums up the importance of art and architecture in concert with each other: “Public art, architecture, landscape and urban space can only become fully integrated when their academic definitions have been challenged, their distinctions as separate entities have been discarded, and it finally becomes difficult to determine when one art form begins and the other ends.” That describes the Salt Lake City International Airport project

to a tee.

Bruce N. Wright, FAIA, an architect, writer and educator, teaches architecture and construction management at Dunwoody College of Technology, and is a regular contributor to Specialty Fabrics Review and Advanced Textiles Source.

SIDEBAR: Types of fabric art + architecture

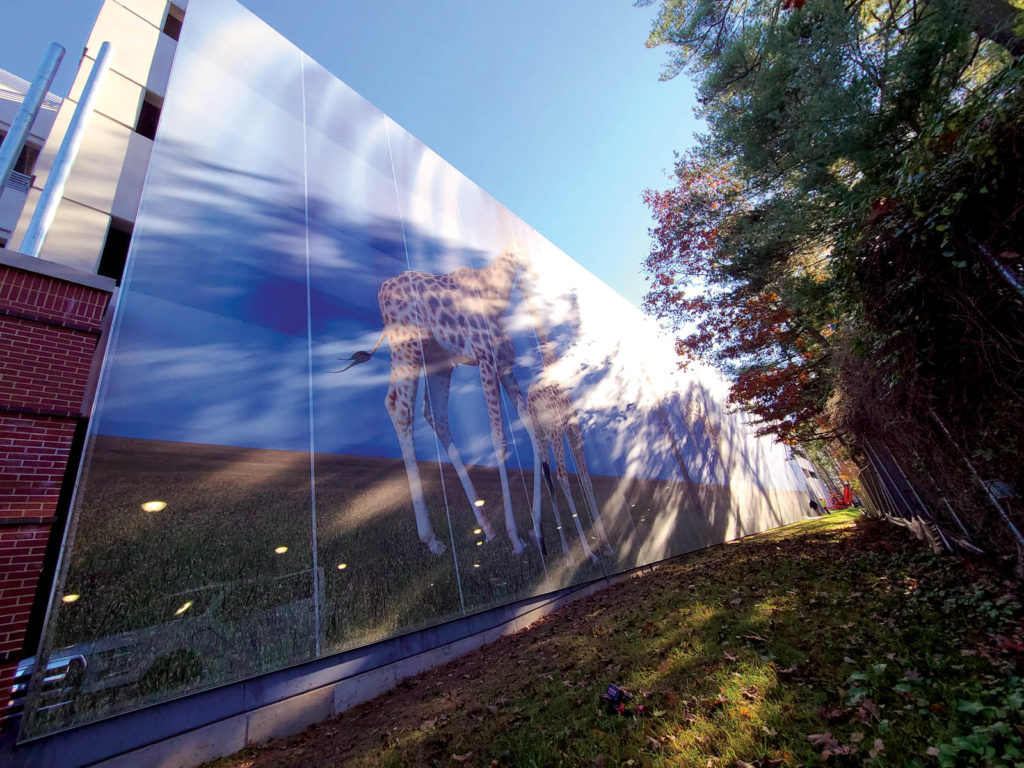

There are several regular fabric art form types that engage with architectural spaces, the most common being facade treatments that are used to dress up a building, or often unattractive parking structures, with simple or elaborate designs. The first form type falls under what can be called the Mural and Re-facing approach. The surface is primarily two-dimensional and wraps the full height of a structure to transform its presence.

A perfect recent example of this type is the Essex County Turtle Back Zoo garage facade. Located in West Orange, N.J., the zoo parking structure needed upgrading. Comito Associates Architects put out a bid, and FlexFacades by Structurflex of Kansas City, Mo., got the job with its capabilities of grand format printing on mesh fabric. “FlexFacades assisted the project design team with creating a screening solution that was not only cost-effective, but also required the least amount of steel of any alternative screening system on the market,” says FlexFacades managing director Tim McFadden. The architects provided the high-resolution digital images for the printing, and the facade system is attached with extruded aluminum fittings used on all perimeters. The extrusions are attached to the concrete framing of the garage with Hilti concrete anchors. “The biggest challenge with the installation was the hill located very close to the garage,” says McFadden. “There were a lot of existing trees, and getting our lifts to the proper location was difficult but ultimately possible.”

A second form type is the Sculptural Building Fabric art approach. These are much more three-dimensional and become dynamic shapes that completely engage the building. There are two subsets to the Sculptural Fabric art: interiors (commonly found in atria or high-ceilinged spaces) and exteriors, where the art additions often become an iconic representation of the building in question.

Fabritecture’s facade for the Oran Park Library in New South Wales, Australia, made of multicolored ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) pillows, is a splendid example of this type. Contracted to provide an engaging west-facing facade treatment that could help reduce the solar heat gain, Fabritecture, of Varsity Lakes, Queensland, designed and constructed a two-layer ETFE facade at the front of the library. The tessellated pattern of colored triangles—red, yellow, white and transparent—helps regulate the building’s temperature. The supporting framework for the pillows is mounted 3 meters (9.8 feet) away from the building, creating a natural stack venting flow of air between the two surfaces.

The brightly colored library could not have asked for a better brand identity, and the treatment provides a highly effective solar barrier. At night the effect is even more stunning, standing as a landmark in the neighborhood. The project won an Outstanding Achievement award in IFAI’s International Achievement Awards program in 2018.

Project data

Essex County Turtle Back Zoo garage facade

Location: Essex County Zoo, West Orange, N.J.

Architect: Comito Associates

General contractor:DMD Contracting

Screen cladding:FlexFacades by Structurflex

Fabric: Type 1A–Ventilated PES; 34% open

Photo: FlexFacades by Structurflex.

Project data

Oran Park Library facade

Location: Oran Park Library and Resource Center, Oran, New South Wales, Australia

Architect: Brewster Hjorth

Engineering/structure:Wade Engineering

Membrane consultants: Seele

Main contractor:ADCO Construction

ETFE installation: Fabritecture

Membrane:ETFE from Seele; multicolors with a PATI frit pattern print

Photo: Kevin Chamberlain.

Leave A Comment